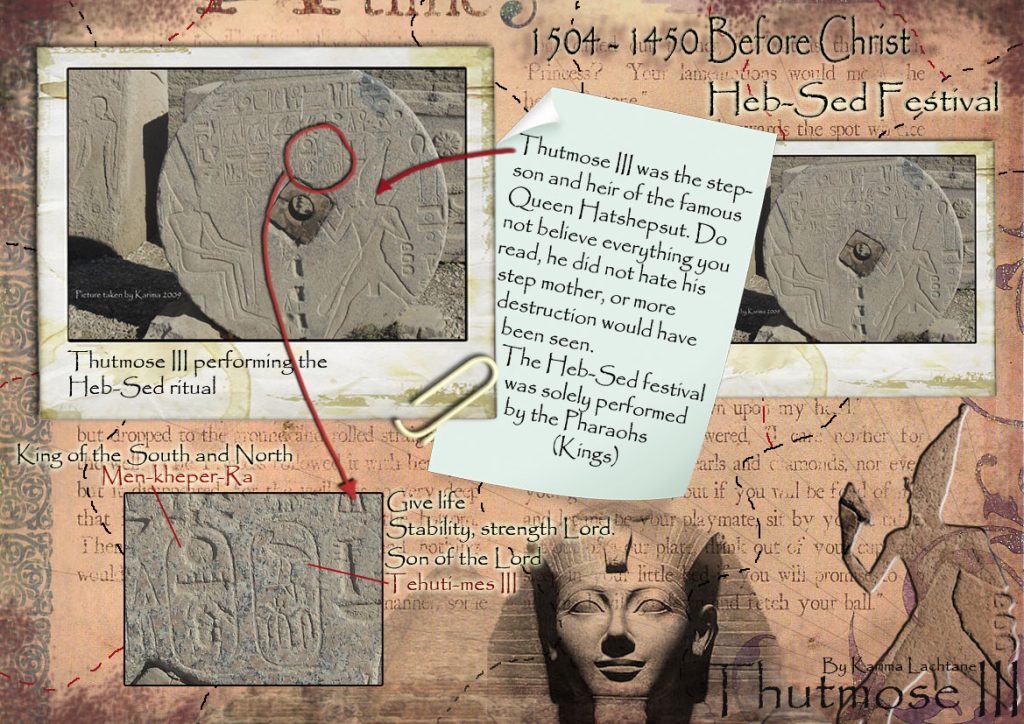

The Forgotten Thutmose III Heb-Sed Festival Stone

Finding a Forgotten Ritual: When Art Defies Time

I wasn’t looking for a mystery that day.

I was simply wandering — as I often do — eyes open, heart steady, camera in hand. Dendera Temple had already given me more than enough to marvel at: grand stone columns, stars carved into ceilings, echoes of footsteps older than memory.

But then I stepped outside the main sanctuary, and something caught my eye. Something round. Something quietly powerful. A granite stele, weathered, but not erased.

I moved closer.

There was something unusual about the engraving — something that didn’t align with the known artistic style of the Ptolemaic period. The carvings weren’t soft and rounded like those of the later Greek-influenced dynasties. These lines were sharper, more precise, more intentional. I felt it in my chest before I could explain it in my mind.

“This isn’t Greek,” I remember whispering to myself.

“This… this feels older.”

It looks like the stone have been used as a grinder of some sort, at least something that was driven around.

It wasn’t just the technical difference — it was the energy. This wasn’t the art of homage or decoration. It was the art of ritual. Of reverence.

And then I saw him — Thutmose III, the powerful pharaoh often remembered for his military campaigns and political achievements. But here, on this carved round slab, he was shown not in conquest, but in ceremony. Performing the Heb-Sed Festival — a sacred act of renewal, a ritual few people ever witnessed, let alone preserved in such detail.

I remember feeling almost breathless.

Because I wasn’t just looking at a historical figure.

I was witnessing a moment where power met humility, where a king ran not for glory, but for alignment with the divine.

Something stirred in me. I’ve never been one to obsess over royal lineages or political legacies. What has always moved me are the beliefs, the inner sanctums, the hidden meanings. And suddenly, here they were — all folded into this scene. A ritual of re-crowning, of being tested not by others, but by the sacred order itself.

Why this stele stood outside Dendera, I can’t say for certain. But I know it wasn’t placed here to impress tourists or fit into a timeline neatly boxed by academics. It was left here to survive. To speak.

The Heb-Sed festival — I would come to learn — was one of Egypt’s most important, and most misunderstood, ceremonies. Said to occur after 30 years of rule, it marked a kind of spiritual rebirth. A trial. A question: Are you still fit to lead?

But I didn’t know all of that yet, not as I stood there in the sunlight, camera dying, dust swirling softly at my feet. All I knew was that something older than reason had found me.

And I let it.

Sometimes, we don’t need full translations or perfect citations to recognize the sacred.

Sometimes, art tells you what it is — if you’re still enough to feel it.

And in that moment, Thutmose III was not a name from a textbook. He was a man being seen.

And the stele was not a stone. It was a ritual remembered.

What Was the Heb-Sed Festival? Beyond the 30-Year Myth

The Heb-Sed Festival is one of those ancient rituals that seems to live at the edge of memory — part history, part mystery. It’s often explained with clinical precision in textbooks: a rejuvenation ceremony performed by pharaohs after thirty years on the throne. But that explanation has always felt too narrow, too convenient. Like describing a heartbeat as merely a muscle contracting.

Because the Heb-Sed was more than a scheduled celebration.

It was a ritual of reckoning.

The ancient Egyptians didn’t see kingship as something one inherited and kept by default. A ruler had to continually earn the right to lead — not through public approval, but by aligning with the divine principle of Ma’at: balance, truth, order, justice. If that alignment faltered, so did the pharaoh’s legitimacy.

And so, the Heb-Sed.

It wasn’t simply a performance. It was a trial, a symbolic renewal of divine authority. The king would run a sacred course — often within a walled court — sometimes carrying ceremonial emblems, dressed in ritual garments. This was not sport. It was ritual movement — a reenactment of cosmic order, a way of proving strength and readiness before the gods.

Yes, tradition says it was performed after thirty years of reign — but look closer, and that timeline begins to blur.

Many pharaohs, including those who ruled far less than three decades, left behind Heb-Sed scenes carved into temple walls, stelae, and shrines. Were they preparing in hope? Were they invoking its power preemptively? Or was the “thirty-year rule” more symbolic than historical?

Perhaps, like much in Egyptian theology, the number was sacred, not sequential.

This opens a more poetic possibility: that the Heb-Sed wasn’t reserved for those who aged into it, but for those who needed to realign, to recommit. A king could summon the ritual not by the calendar, but by the soul’s condition.

And maybe, in a world so fixated on timelines, that’s the detail we most overlook.

Because what this ritual really speaks to is something universal — the need to pause and ask:

Am I still who I claim to be?

Have I drifted from my purpose?

Do I carry the weight of my crown, or does it carry me?

These aren’t questions of vanity. They’re questions of integrity.

And the ancient Egyptians, more than most civilizations, understood that without integrity, even kings are hollow.

So when we see Thutmose III running in his Heb-Sed scene, or Djoser long before him, or any ruler after — we’re not just witnessing a rite of passage.

We’re witnessing a man confronting the sacred.

A moment of divine accountability.

That’s why the Heb-Sed was never just a celebration. It was a reckoning wrapped in ritual. A chance to be renewed — not in body alone, but in spirit.

And in a way, maybe that’s why the ritual still calls to us now.

Because we, too, need moments like this — not on royal courts, but in quiet places inside ourselves.

Moments to pause.

To run our course.

To carry what’s sacred, and see if it still fits in our hands.

Sed, Wepwawet, and the Goddess Sechat-Hor: Divine Forces Behind the Ritual

We often think of rituals as actions — steps to be followed, gestures to be performed. But in ancient Egypt, ritual was relationship. And the Heb-Sed Festival was no exception. It wasn’t just about a king proving his strength — it was about reaffirming his sacred bond with the gods who gave him the right to rule.

But who were those gods?

The answers, like so much of Egypt’s spiritual history, are layered and elusive — a palimpsest of beliefs, rewritten and reshaped across centuries. At the heart of the Heb-Sed is a forgotten god: one known simply as Sed.

His name gives the festival its title, yet his identity remains mostly lost to us. Sed was associated with renewal, justice, and divine alignment — a force rather than a figure, a principle rather than a personality. Some believe he was closely tied to Ma’at, the concept of cosmic balance and moral truth. He may have stood as her champion — or her shadow — reminding kings that justice was not optional. It was divine law.

Over time, Sed fades from the mythological landscape, and another god steps in — Wepwawet, the ancient jackal-headed deity known as the “Opener of the Ways.”

Wepwawet is older than many of the gods we know today. He wasn’t just a guide to the dead — he was a path-clearer, a force that made new beginnings possible. In the context of the Heb-Sed, his role becomes beautifully clear: the king was not just renewing his rule — he was being led into it again, through divine permission. Wepwawet opened the ritual path, cleared the way between heaven and earth, and watched as the pharaoh stepped forward — hopefully still worthy.

Then, from another side of the mythic sky, a goddess appears.

Her name is Sechat-Hor, a mythological cow goddess who offers milk to Horus — the divine nourishment of immortality. She’s not well known, not prominently worshipped, but she whispers through this ritual like a mother hidden in shadow. Her milk wasn’t just sustenance — it was sacred. To drink from her was to be reborn, to be made whole again in the eyes of the gods.

And what is a king, if not a child of divinity, needing that moment of reconnection?

These three — Sed, Wepwawet, and Sechat-Hor — form an invisible triangle around the Heb-Sed. They are not always carved into stone. They are not always named. But their presence is undeniable. You feel it in the symbols, in the structure of the ritual, in the rhythm of the pharaoh’s movements.

And perhaps that is the deeper truth.

The gods of Egypt weren’t always loud. Sometimes, they were felt more than seen. They lived in the logic of rituals, in the sacred timing of festivals, in the pause before a crown was placed.

The Heb-Sed was not just an act of kingship. It was a conversation with the divine.

And when Thutmose III stepped into that sacred court — when he ran, when he bowed, when he rose again — he wasn’t just performing for priests or people. He was answering to something older than himself. Something sacred. Something eternal.

A god with no face.

A jackal who opened the way.

A cow who gave milk to the gods.

They were all there.

And in some way, so are we — every time we stop, realign, and remember what we are meant to be.

Thutmose III and the Crown Ritual: Running for Power

When we think of power, we often imagine stillness — a throne, a statue, a figure unmoving and unquestioned. But the ancient Egyptians saw things differently. For them, power had to move. It had to breathe, prove itself, be renewed.

And so, the pharaoh ran.

In the Heb-Sed Festival, one of the most sacred acts was not seated ceremony or verbal oath, but movement — a ritual run performed by the king within the Sed court, a space set apart from the world, bounded by sacred geometry and ancient breath.

Thutmose III, remembered as a warrior king, conqueror, and statesman, is shown in one such scene — running. His legs extended mid-stride, arms often bearing sacred objects: sometimes the crook and flail, sometimes symbols now lost to us, but never without meaning.

He wasn’t running from anyone.

He was running toward something: alignment, endurance, divine recognition.

It was a test — not of athletic ability, but of vitality, will, and spiritual strength. The pharaoh didn’t run to entertain the crowd. He ran to show the gods that he was still alive in purpose, still strong in soul.

And then came the crowns.

At a later point in the ritual, Thutmose III would have stood before his priests, nobles, and gods to receive again the two crowns of Egypt: the White Crown of Upper Egypt and the Red Crown of Lower Egypt.

Each crown on its own represented a region. Together, they formed the double crown, the pschent — the symbol of a unified kingdom, and a reminder that a pharaoh must rule over more than just land. He must rule over opposites: order and chaos, life and death, body and spirit.

The act of receiving the crowns wasn’t just a reminder of conquest.

It was a renewal of responsibility.

And that’s what makes this moment so human.

Because even a king had to earn his crown again — not through war or politics, but through ritual realignment. He had to move, carry, sweat, kneel, rise. He had to become worthy, again and again.

There’s something in this that still speaks to us today.

We live in a world that rewards appearances. But ancient Egypt reminds us that true leadership, true purpose, comes from inner work — from showing up in sacred spaces and doing what must be done, even when no one sees.

When I stood before that stele outside Dendera, and saw Thutmose III in motion, I didn’t see a distant figure frozen in stone.

I saw a man stepping forward — one more time — into the gaze of eternity.

Running, not for applause, but for the right to wear the truth again.

And maybe that’s what power really is.

Not dominance. Not stillness.

But movement that stays aligned with the divine.

The Stele at Dendera: An Artistic and Emotional Anomaly

Some artifacts call to you with their history.

Others with their beauty.

But some — like the stele I found outside Dendera Temple — call with something stranger, deeper.

A feeling.

It wasn’t grand or central. It wasn’t behind glass or protected by rope. It sat there quietly, as if waiting for someone not just to look — but to see.

At first glance, it seemed out of place. Dendera is largely attributed to the Ptolemaic period — the last breath of ancient Egypt, shaped by Greek influence. Many of the carvings from that time are softer, more rounded, often decorative rather than deeply symbolic.

But this stele was different.

The lines were sharp. The forms elegant but not embellished. The figure — likely Thutmose III — was rendered in a style I had seen before, but only in reliefs from the time of Queen Hatshepsut. There was clarity in the body, purpose in the posture. It didn’t match the Ptolemaic aesthetic. It felt… older. Truer. Still alive in some way.

That’s when I knew: this was more than art. It was a survivor.

The scene showed the pharaoh engaged in the Heb-Sed ritual — either running or mid-stride, though the stone was broken. His face had suffered damage, but the rest remained: his leg extended, torso strong, arms holding sacred emblems. A moment frozen in ritual motion.

The damage didn’t erase him. It made him more real.

Because isn’t that the way of sacred things?

They aren’t protected from time — they endure it.

And then there was the composition itself — balanced, centered, intentional. You could feel the rhythm of it. Even though parts were missing, your eye knew where to go. It was as if the artist had written a song in stone, and even with verses gone, the melody still echoed.

I’ve looked at many Egyptian reliefs, but this one felt personal.

Not in the sense that it was made for me — but that it was meant to be found, meant to be felt.

It had waited long enough.

And in that stillness, I realized something: this stele wasn’t just carved by hands. It was carved by faith.

Faith that someone would remember.

Faith that ritual mattered.

Faith that even if no one read the glyphs, the gesture would remain.

We often forget that ancient artists were not merely craftsmen. They were storytellers of eternity. Their tools weren’t just chisels — they were prayers. Every line they cut into granite was meant to last longer than breath, longer than kings, longer than even memory.

And this stele — broken, misattributed, quietly radiant — proved that it had.

It reminded me that the line between sacred and forgotten is thin. Sometimes all it takes is a glance. A question. A moment of stillness. And suddenly, a piece of stone becomes a voice, a lesson, a whisper from another time.

That’s what I found at Dendera.

Not just a stele.

But a presence.

What This Scene Still Teaches Us About Kingship and Integrity

In the end, it isn’t just about the stele.

Not really.

Not about Thutmose III or the Heb-Sed court or the perfect arc of a running leg carved into granite.

What remains — what truly lingers — is the question that the scene still asks.

What does it mean to lead with integrity?

We are so used to thinking of kingship as something distant — a crown, a title, a lineage guarded by gold and guarded halls. But the Heb-Sed Festival, especially as shown in this worn relief, reminds us that real kingship was something else entirely.

It was earned.

Not once.

But again, and again, and again.

The ritual demanded motion. Not for ceremony’s sake, but for soul’s sake.

The pharaoh had to run. To carry. To show strength not as dominance, but as endurance — the kind that came from being rightly aligned with something higher. Something sacred.

And maybe that’s why the scene still speaks to us, across centuries and sand.

Because whether we wear crowns or not, we all rule something.

Our choices.

Our stories.

Our relationships.

Our small kingdoms of responsibility.

And like the pharaoh in the Heb-Sed court, we must sometimes pause and ask:

Am I still fit to carry this?

Have I wandered too far from the center?

Do I still stand in alignment with what matters most?

These are not questions of weakness. They are questions of courage.

Thutmose III ran not because he was unsure — but because he understood that true power requires renewal. That even kings must return to the beginning. That even the strongest must remember why they lead at all.

And that’s what makes this stele more than stone.

It’s a mirror.

A reminder that integrity isn’t a possession — it’s a practice.

We don’t carry it once and forever.

We carry it again and again, even when it grows heavy. Especially then.

In this final reflection, I think of the ancient artist — the one who carved that moment into granite with hands now lost to time. I wonder if they knew, even then, that someone far in the future might stand before it and feel… called.

Not to rule.

But to realign.

And maybe that’s all any of us need now and then.

Not a festival.

Not a ceremony.

Just a moment of quiet honesty where we look at our own path, our own sacred run, and ask if we’re still running in the right direction.

Because in a world that often mistakes noise for leadership and appearance for worth, this quiet stone at Dendera reminds us:

The truest leaders — the truest selves — return to the center.

Not once.

But as many times as it takes.

If you are interested in learning more about the Web-Sed Festival then you will love this Ramesses II Heb-Sed Festival

Frequently Asked Questions

Where was the Thutmose III Heb-Sed Festival stele found?

It was photographed outside Dendera Temple, where its unusual style and symbolism suggest it may predate the Ptolemaic period.

Was the Heb-Sed Festival only performed after 30 years?

Traditionally yes, but many pharaohs depicted it earlier, suggesting the ritual was more symbolic—about renewal and divine alignment rather than reign length.

Which gods were involved in the Heb-Sed Festival?

The forgotten god Sed, the jackal god Wepwawet, and the goddess Sechat-Hor all played symbolic roles in guiding and nourishing the pharaoh through his renewal ritual.

Why did pharaohs run during the Heb-Sed Festival?

The ritual run symbolized strength, divine alignment, and the pharaoh’s readiness to continue ruling. It was a sacred act of renewal, not performance.

Why is the Heb-Sed Festival stele at Dendera considered unusual?

Its artistic style is older and more precise than the surrounding Ptolemaic reliefs, suggesting it may date to the time of Thutmose III or even earlier.

What does the Heb-Sed Festival teach us about leadership today?

It teaches that leadership must be renewed through action, alignment, and purpose — not claimed once, but continually earned through integrity.